“All the other pleasures of life seem to wear out, but the pleasure of helping others in distress never does.”

— Julius Rosenwald

While today’s philanthropy includes many generous individuals and foundations who give with humility, others center themselves in their giving seemingly to benefit their own ego, status or standing. As Gara LaMarche recently noted while exploring lack of collaboration among funders in Inside Philanthropy, a publication for nonprofits and grantseekers, “‘Not invented here syndrome’ is endemic among foundations, whose leadership and trustees often opt to embrace differentiation while paying lip service to collaboration.”

Less well known than other philanthropists from history, Julius Rosenwald’s impact was important and transformative—his humility contributing to both.

Born in Springfield, Illinois to German Jewish immigrant parents in 1862, Mr. Rosenwald amassed his fortune leading and growing Sears, Roebuck and Company. He founded the Rosenwald Fund, a family foundation dedicated to “the well-being of mankind,” and donated more than $60 million (approximately $1 billion in today’s dollars) to public schools, colleges and universities, museums, Jewish causes, and African American institutions.

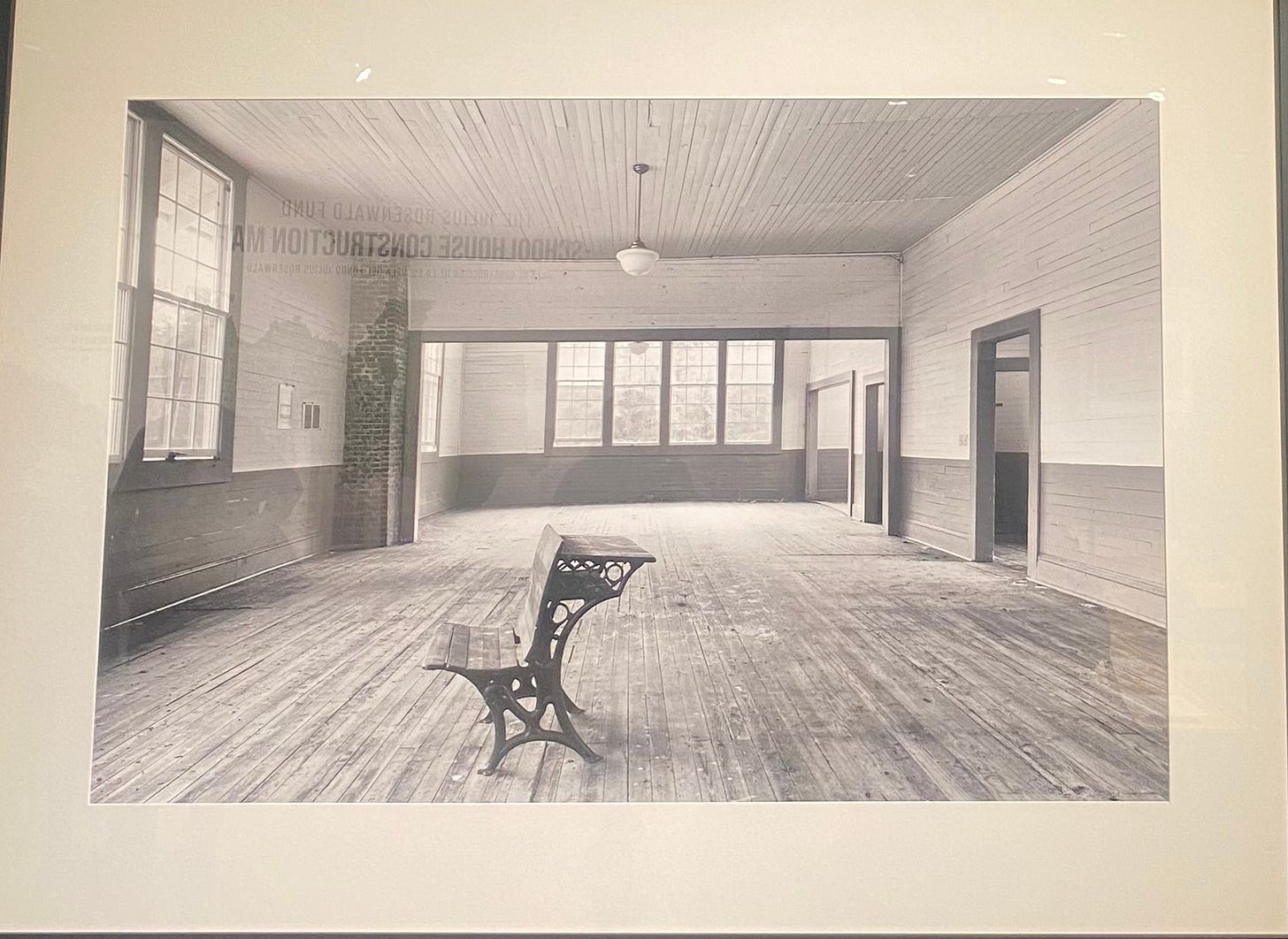

During segregation, schools for African Americans were chronically underfunded meaning children received substandard educations or none at all. Guided by Mr. Rosewald’s goal of a school for African American children in every Southern county, Rosenwald schools are among the Rosenwald Fund’s—and perhaps America’s—greatest philanthropic successes.

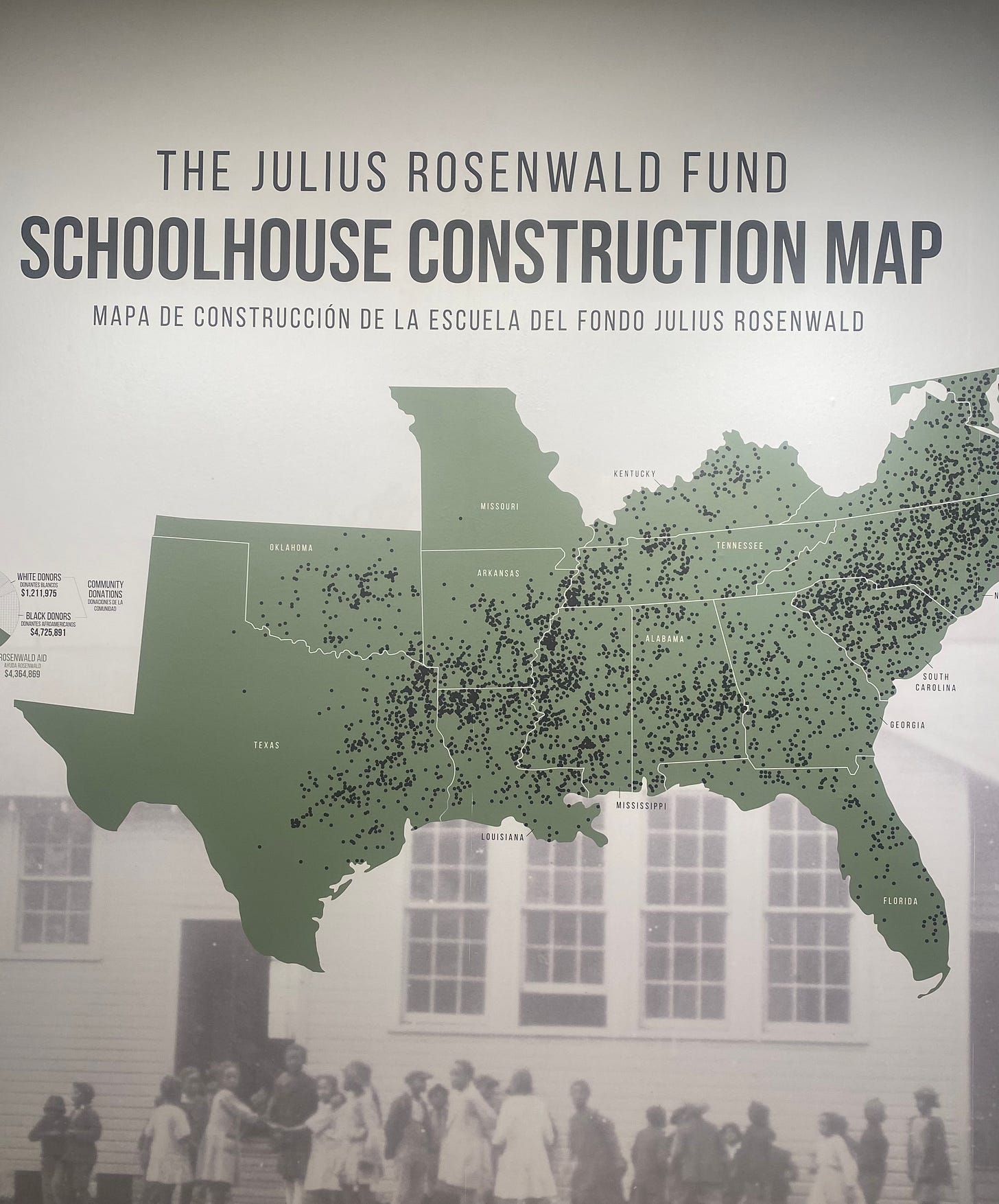

In partnership with Booker T. Washington, designed by architects of Tuskegee University, and with financial support from communities and school districts, the Rosenwald Fund built approximately 5,000 schools across the South. (According to Oliver Zunz in Philanthropy in America, 5,357 of them in 15 states. Another source, A Better Life for Their Children by Andrew Feiler, puts the number at 4,978.) At the time, 40% of all Black children, more than 600,000, attended a Rosenwald school, many going on to college and earning higher degrees.

“I am interested in America. I do not see how America can go ahead if part of its people are left behind.” - Julius Rosenwald

It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to know what is best for another without truly understanding their experience and perspective. Still, today as in the past, those with the power of position or wealth sometimes take on issues minus perspective and involvement from those most impacted.

Not so Julius Rosenwald. In his requirement of school board ownership and maintenance, community provision of labor, land, and/or the cost of bricks and lumber—a concept known as challenge or matching grants—Mr. Rosenwald effectively ensured each school included the perspective of those it served. A seat at the table if you will.

Mr. Rosenwald had previously implemented challenge matches in the construction of YMCAs for African Americans. In 1911 he offered $25,000 to cities in which the communities would provide a $75,000 matching share; together those communities and Mr. Rosenwald built African American YMCAs in 24 cities. (YMCA initially approached Mr. Rosenwald in 1910 with a request to fund a single YMCA (for whites) in Chicago. Mr. Rosenwald’s response? “I won’t give a cent to this $350,000 fund unless you will include in it the building of a Colored Men’s YMCA.” They agreed and the Wabash YMCA was built in 1913. The rest, as they say, is history.)

Mr. Rosenwald rejected the still common philanthropic practice of naming buildings and projects for himself. While the schools the Rosenwald Fund built are often referred to as Rosenwald schools today, they were not while operating. It was important to Mr. Rosenwald that the schools belong to the communities and be named accordingly.

Well known during his lifetime, Mr. Rosenwald’s philanthropy is less so today. Unlike foundations created by other philanthropists of his era—endowed and thus designed to fund themselves in perpetuity (a practice that continues and is debated to this day)—the Rosenwald Fund was intended to sunset within 25 years after Mr. Rosenwald’s death. The Rosenwald Fund was fully spent by 1948—honoring his “give while you live” approach.

Learn more: “A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools that Changed America” is on view at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum until August 17, 2025.

Get involved: Inspired by the 2015 documentary “Rosenwald” by filmmaker Aviva Kempner, representatives of the National Parks Conservation Association and the National Trust established the Rosenwald Park Campaign, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Campaign envisions a National Historical Park comprising a state-of-the-art visitor center in Chicago that would interpret Rosenwald’s overall legacy and a small number of Rosenwald Schools throughout the south complemented by a Network of Rosenwald Schools.

Fun fact: Mr. Rosenwald was born one block away from the Lincoln family home while Abraham Lincoln was President. The Rosenwald family later moved directly across from the Lincoln home (into a home built by Alexander Graham Bell) and today both homes are part of the Lincoln Home National Historic Site.